Brindlewood Bay is a Powered By The Apocalypse (PBTA) game of cozy mysteries written by Jason Cordova and published by The Gauntlet. In it, you play elderly widows investigating murders in a quiet New England coastal town, while gradually revealing the dark mysteries of an ancient cult. It’s also a fantastic game for one-shot play, with an innovative mystery system that makes investigations improvisational and fun. I’ve run two one-shots of it so far, and will definitely be adding it to my one-shot repertoire.

While you’re reading this, I should tell you about my Patreon. Patrons get access to content 7 days before they hit this site, the chance to request articles or content, and the chance to play in one-shot games, for a very reasonable backer level. If you like what you read, want to support the blog, and have the funds for it, please consider supporting here.

The Fluff

You play elderly widows, members of a book club, solving crimes. The game’s sources are are Agatha Christie murder mysteries, 1970s-1990s TV series, very much in the ‘cozy’ tradition. In chargen, you broadly define your PC and their cozy activity (knitting, gardening, cooking, etc.) – and then, as a group, you all add items related to each others’ activities. In play, these offer a bonus to rolls, and it’s great to see players find opportunities to use, for instance, their late husband’s tiki set, in order to help their investigations.

This is not a common genre in RPGs, but it’s very recognizable from popular culture; my players had no trouble feeling the setting and tropes of the game, especially after the cozy places group activity at the start. Characters are both broadly competent and physically vulnerable – while Brindlewood Bay is a generally safe environment, shadowy figures stalk around and the suspect is still at large.

The setting is well painted in broad brush strokes, and the mysteries that are provided (with more available in a supplement, Nephews in Peril) add further details and locations to the town. Implicit in longer-term play is a metaplot about discovering the sinister cult in the town – which is perhaps the reason for there being so many murders – but this doesn’t come into play in a one-shot.

The Crunch

This is a really streamlined evolution of the PBTA engine that keeps what’s important front and centre. There are two ‘action’ moves – Day and Night, which being rolled determined by the time of day, and a Meddling Move, which is the main vector to gather clues. There are a few additional moves, but these three form the bulk of play. While MCing, I really appreciated the simplicity of this – I never had the “uhh, this seems like you’re trying to… go aggro?” moments that I often get when running PBTA games with a broader selection.

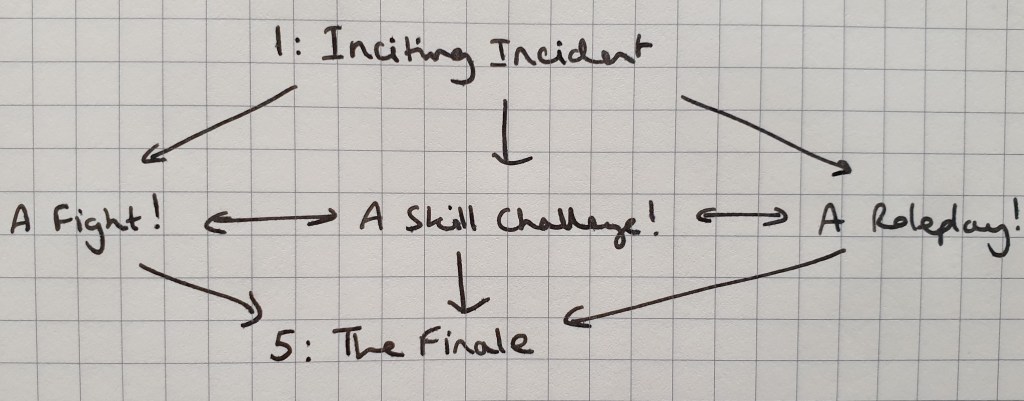

Mysteries get solved by you gathering Clues, usually by using the Meddling Move, which are snippets of information, deliberately left loose – a note writing somebody out of a will, a missing dog, signs of a struggle on the victim’s body. After some investigating, the PCs get together, decide which suspect they think was the murderer, and make a Theorize Move, adding the number of Clues gathered and subtracting the Mystery’s complexity – on a Hit, they can catch them – on other results, they may have got the wrong person, leaving the murderer free. In my two games, in one case they apprehended the butler in time – the second, with a 7-9 result, led to a car chase and the eventual escape of the killer when a PC’s cat ran out in front of their car!

The Clue / Theorize economy is amazingly elegant. I have my own issues with investigative games, and the tension between finding the right answer and playing an entertaining game irks me, and in more player-led / story-now games even more so. I discussed it during our after action report of Vaesen with the Smart Party – at a point in the session, you click from “playing my character / making a fun scene” to “solving a puzzle.” Brindlewood Bay avoids this by not needing to join the dots until the Theorize move – up until then, players can just go poking around wherever they want, and clues – if they’ve got the dice for it – will keep showing up. As MC I still felt involved in building the mystery, by choosing which clues made sense to place, and seeing the players have license to freewheel and solve the mystery themselves gave it a satisfying feeling of collaboration.

The One Shot

Although clearly ideally built – like most PBTA games – for short-run campaign play, Brindlewood Bay has so much to recommend it as a one-shot. A setting and genre that is both instantly recognisable and a fresh break from standard RPG genres, an easy-to-MC PBTA framework and a structure that genuinely supports collaborative storytelling made it a hit in both games that I ran. Indeed, although the TV series source material was often long seasons of shows, in practice before media-on-demand we watched them in snippets of individual shows out of order, so it doesn’t feel out of genre to be looking at a murder-of-the-week with protagonists who already have a past together.

I’d recommend for a one-shot not cutting down the ‘cozy place’ prep step at all – as I’ve written about previously, spending up to an hour at the start of a PBTA one-shot is always worth it to get a great setup and have the players able to really get into their characters for the rest of the session. I used Dad Overboard, one of the Mysteries included in the game, and it was a great solid plot structure for a satisfying conclusion in one session.

One thing that I’d also recommend is being really open about the collaborative nature of the mystery – on the sign up description (if you’re running at a con), at the start of the session, even a reminder during the game if you see a player start to cut out investigative channels. For some fans of investigative games, this collaborative stuff, and the MC not even knowing who did the murder, requires a real shift in approach that you need to make sure they’re up for.

In summary, this is a brilliant game, and one of my highlights of 2020 – I’m not sure if I’ve ever found MCing a PBTA game as relaxing and flat-out enjoyable as Brindlewood Bay in a long time. The simplicity – elegance even – of the moves, the wealth of pre-made Mysteries available, and the easily-grokked genre make it an absolute one-shot hit. One of my players went straight from my game to download and read the rules himself – so intrigued was he by the system – you can’t say fairer than that.